Sergio A. Marenssi, Marianela Díaz, Carlos O. Limarino

2 022

Journal of South American Earth Sciences, Volume 122, February 2023, 104168

The very thick (up to 6000 m thick) Miocene Vinchina Formation was deposited between 16 and 8 Ma ago and later covered by more than 2500 m of Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments in a broken foreland basin. The very thick sedimentary pile accumulated in a medium to low-gradient basin must have suffered intense mechanical compaction during burial.

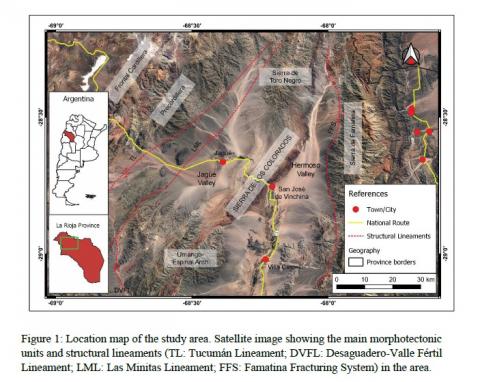

Seventy thin sections of unaltered sandstones collected in three sections along the depositional strike of the Vinchina Formation at the Sierra de Los Colorados, La Rioja Province, northwestern Argentina, were analyzed under the microscope for determining compactional paths and controls.

The role of compaction in sandstone diagenesis was firstly assessed using the change in intergranular volume (IGV), which is the sum of all cement and remaining primary porosity. It is clear from the IGV analysis that most of the studied sandstones lose more porosity by compaction (COPL) than by cementation (CEPL). In general compaction increased from the upper to the lower member of the Vinchina Formation (i.e with depth) and there is a clear trend of the compaction index ICOMPACT increase from the northern, shorter Los Pozuelos to the central, thicker La Troya sections. Surprisingly, the thickest southern El Yeso section shows anomalous results possibly due to the extensive development of cements as indicated by the highest CEPL values. Cements are related to the depositional environment (gypsum, calcite) and clast composition (zeolites). Early cements may have prevented further compaction while late cements may have produced open fabrics by dissolution of matrix and framework clasts. Both cases show that diagenetic processes are not homogeneous basin-wide and that the diagenetic pathways are not only controlled by the increase in burial depth but also by characteristics associated with depositional environments and framework clast composition.

We also attempted to relate compaction to burial depth based on the nature (point, long, concave-convex and sutured contacts) and the number (contact and packing indexes) of grain-to-grain contacts in the studied sandstones. The sandstones present predominance of concave-convex grain-to-grain contacts and IC indexes mostly between 3 and 4. Sutured contacts are uncommon, and stylolites were not observed at all. Persistence of open fabrics, floating textures and point grain-to-grain contacts at different depths are the result of dissolution-cementation processes. A clear trend of increasing mechanical compaction with depth is only seen along the northern coarser-grained but thinner Los Pozuelos section. Although compaction seems to have increased with depth and also from north to south, the thickest but overall finer-grained El Yeso (southern) section do not show a clear pattern of change with depth. This behavior seems to be the result of at least four main factors: 1) mean sandstone grain-size, 2) thickness of muddy intervals, 3) development of early diagenetic cements, and 4) depth of burial.

Comparison with comparable examples suggests that similar compactional characteristics are achieved between 3.5 and 6 km of maximum burial depths. However, cumulative thickness of the Vinchina basin-fill indicate that the base of the Vinchina Formation may have been buried at 8.5 km deep but preliminary backstripping models suggest that by 5 Ma this surface may have reached up to 10 km depth. Alternatively, recorded repetitive episodes of deformation, uplift, and erosion (progressive unconformities) in the Vinchina basin may have prevented the sedimentary pile to be deeply buried and therefore allow to reconcile the observed compactional textures with depth of burial.

The results obtained in this work show that the analysis of mechanical compaction in sandstones constitutes a complex task and in occasions there is not a linear relationship between the contact indexes and depth of burial. Sandstone compaction is controlled not only by the depth of burial but also by other factors such as, time, geothermal flow, matrix content, the development of early cements, the ratio between ductile and rigid lithic fragments and, in tectonically active basins the development of progressive unconformities. Therefore, in most cases, it is very speculative to extend diagenetic conditions to basin-wide scales. In particular, the porosity-depth relationship must be based on primary porosity only.

Seventy thin sections of unaltered sandstones collected in three sections along the depositional strike of the Vinchina Formation at the Sierra de Los Colorados, La Rioja Province, northwestern Argentina, were analyzed under the microscope for determining compactional paths and controls.

The role of compaction in sandstone diagenesis was firstly assessed using the change in intergranular volume (IGV), which is the sum of all cement and remaining primary porosity. It is clear from the IGV analysis that most of the studied sandstones lose more porosity by compaction (COPL) than by cementation (CEPL). In general compaction increased from the upper to the lower member of the Vinchina Formation (i.e with depth) and there is a clear trend of the compaction index ICOMPACT increase from the northern, shorter Los Pozuelos to the central, thicker La Troya sections. Surprisingly, the thickest southern El Yeso section shows anomalous results possibly due to the extensive development of cements as indicated by the highest CEPL values. Cements are related to the depositional environment (gypsum, calcite) and clast composition (zeolites). Early cements may have prevented further compaction while late cements may have produced open fabrics by dissolution of matrix and framework clasts. Both cases show that diagenetic processes are not homogeneous basin-wide and that the diagenetic pathways are not only controlled by the increase in burial depth but also by characteristics associated with depositional environments and framework clast composition.

We also attempted to relate compaction to burial depth based on the nature (point, long, concave-convex and sutured contacts) and the number (contact and packing indexes) of grain-to-grain contacts in the studied sandstones. The sandstones present predominance of concave-convex grain-to-grain contacts and IC indexes mostly between 3 and 4. Sutured contacts are uncommon, and stylolites were not observed at all. Persistence of open fabrics, floating textures and point grain-to-grain contacts at different depths are the result of dissolution-cementation processes. A clear trend of increasing mechanical compaction with depth is only seen along the northern coarser-grained but thinner Los Pozuelos section. Although compaction seems to have increased with depth and also from north to south, the thickest but overall finer-grained El Yeso (southern) section do not show a clear pattern of change with depth. This behavior seems to be the result of at least four main factors: 1) mean sandstone grain-size, 2) thickness of muddy intervals, 3) development of early diagenetic cements, and 4) depth of burial.

Comparison with comparable examples suggests that similar compactional characteristics are achieved between 3.5 and 6 km of maximum burial depths. However, cumulative thickness of the Vinchina basin-fill indicate that the base of the Vinchina Formation may have been buried at 8.5 km deep but preliminary backstripping models suggest that by 5 Ma this surface may have reached up to 10 km depth. Alternatively, recorded repetitive episodes of deformation, uplift, and erosion (progressive unconformities) in the Vinchina basin may have prevented the sedimentary pile to be deeply buried and therefore allow to reconcile the observed compactional textures with depth of burial.

The results obtained in this work show that the analysis of mechanical compaction in sandstones constitutes a complex task and in occasions there is not a linear relationship between the contact indexes and depth of burial. Sandstone compaction is controlled not only by the depth of burial but also by other factors such as, time, geothermal flow, matrix content, the development of early cements, the ratio between ductile and rigid lithic fragments and, in tectonically active basins the development of progressive unconformities. Therefore, in most cases, it is very speculative to extend diagenetic conditions to basin-wide scales. In particular, the porosity-depth relationship must be based on primary porosity only.